HISTORY

The Menomonee River Valley has a fascinating history, from wild rice marsh to manufacturing center to infamous eyesore - and now to a national model of economic and environmental sustainability.

Corey Zetts, Executive Director at Menomonee Valley Partners, explains how the Menomonee River Valley has been converted from an inaccessible, blighted, polluted area to a vibrant economic center with public spaces alongside the healthy river.

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Historic Menomonee River Valley

Four miles long and one half-mile wide, the Menomonee River Valley extends from the Harley-Davidson Museum® to American Family Field.

The Valley was formed by melting glaciers more than 10,000 years ago and, for thousands of years, the 1,200-acre Menomonee River Valley was a wild rice marsh, home to a diverse number of Indigenous nations because of its fertile land and waterways. The name “Menomonee” is derived from the Anishinaabe “meno,” meaning good, and “min,” a term for grain or fruit. Wild rice (menomin) flourished in the extensive wetlands of the Valley. Native Americans settled here as it was a source of food with fish and wild rice, of medicine with its plants, and trapping with its wildlife. It was also a source of transportation. All of these resources made it a prime gathering space where tribes would come to trade. Tribes co-existed peacefully, even living in the same villages.

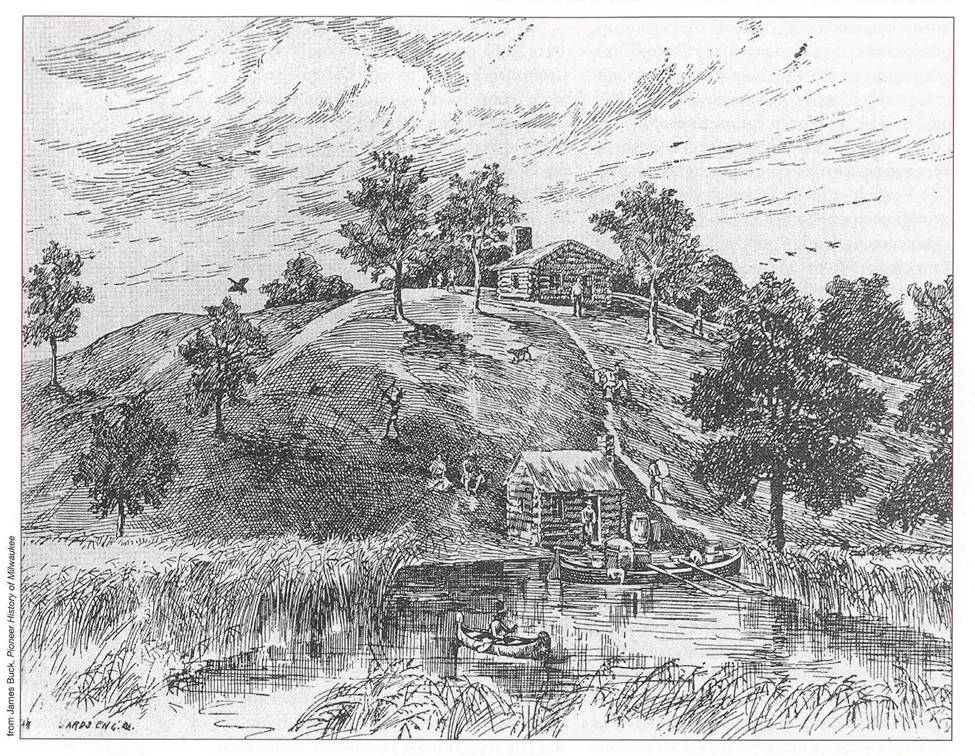

In 1634, Jean Nicolet, a French man, was the first European to come in contact with the Indigenous people of Milwaukee. Together they established the lucrative fur trade that lasted into the nineteenth-century. By the 1700s, the Potawatomi were the primary residents of the region. Ojibwa, Fox, Menominee, Ottawa, Sauk, Winnebago and others also lived here throughout centuries. In 1795, Jacques Vieau, a fur trader, married Angelique Roy, the niece of Potawatomi Chief Anaugesa, and established the first permanent trading post in Wisconsin on the bluffs of the Valley at the site of what is now Mitchell Park. Their daughter, Josette, married his clerk Solomon Juneau in 1825 and helped build the character and foundation of Milwaukee.

From the late 1600s through the War of 1812, Indigenous groups were swept into battles and established alliances with various nations as the French, British, and Americans fought for control over North America. After the War of 1812, the Potawatomi slowly began ceding land to the United States, culminating with the 1833 Treaty of Chicago in which they lost 5,000,000 acres of Potawatomi land. White settlers were interested in the water ways that connected Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes inland to the rest of Wisconsin and Illinois. Over the next few years, the Potawatomi were forcibly removed from their traditional lands, some were deported west on the Trail of Death and others fled to remote areas of Wisconsin and hid in the woods. The survivors of these exiles are the Forest County Potawatomi.

Learn more about Milwaukee’s Native American history

By the mid-1800s, the settlement of Milwaukee pushed toward the Valley, and Milwaukeeans filled the marsh with soil, gravel, and waste to create dry land for additional development. They straightened the Menomonee River and cut canals to provide shipping routes.

In 1795, Jacques Vieau, a fur trader, established the first permanent trading post in Wisconsin on the bluffs of the Valley at the site of what is now Mitchell Park. By the mid-1800s, the settlement of Milwaukee pushed toward the Valley, and Milwaukeeans filled the marsh with soil, gravel, and waste to create dry land for additional development. They straightened the Menomonee River and cut canals to provide shipping routes.

“All the marsh proper...would, in the spring, be literally alive with fish that came in from the lake... And the number of ducks that covered the marsh was beyond all computation.”

Vieau Hill

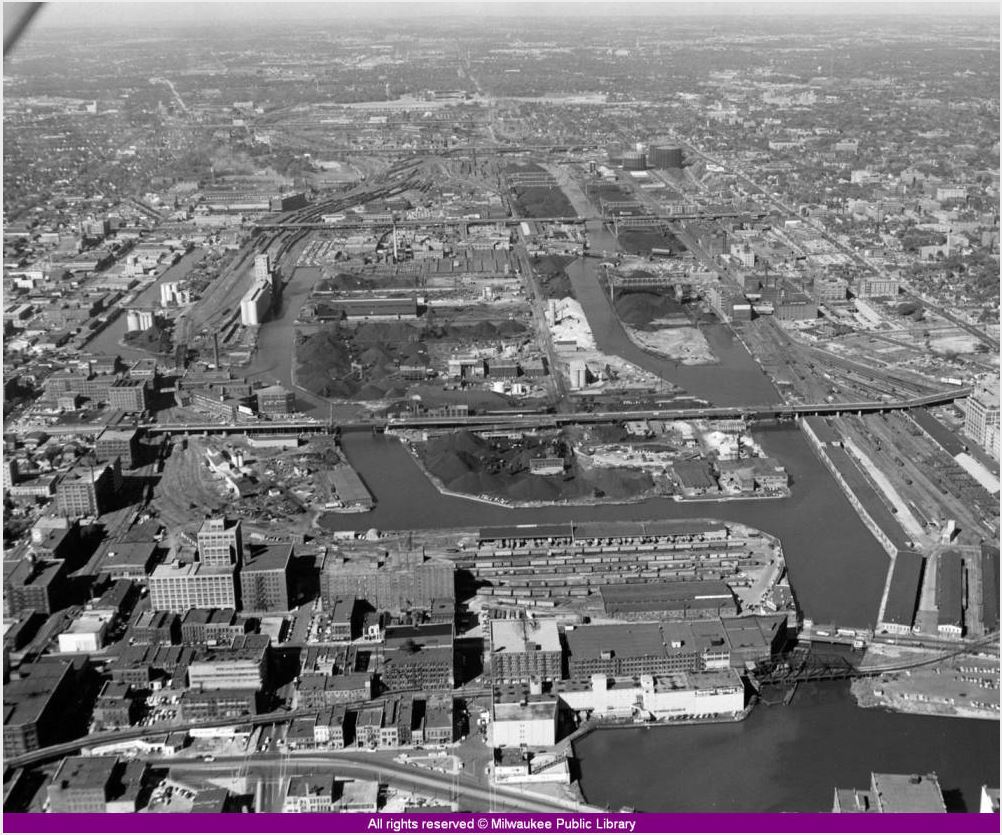

1872 - Map of the Valley facing west

1882 (Photo: Library of Congress)

The Machine Shop of the World

By the early 1900s, Milwaukee was known as the “Machine Shop of the World” and the Menomonee River Valley was its engine. Farm machinery, rail cars, electric motors, and cranes were made in the Valley. Clay became cream city bricks. Wheat was turned into flour, hogs became ham and barley became beer. Cattle were made into meat, leather and tallow (soap and candles) with no parts wasted. These changes provided jobs for thousands of people, but damaged the Valley’s natural resources.

From 1879 to 1985, the Valley was the location of the Milwaukee Road Shops, an enormous complex that made rail cars and locomotives for the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. In the 1900s, the Milwaukee Road was one of the largest employers in Milwaukee with nearly 3,000 employees. Many lived in the neighborhoods nearby and walked to work.

Milwaukee Road workers

Falk (now Rexnord)

Neighborhood Life

By the late 1800s, thousands of workers arrived in the Menomonee River Valley to work in industrial jobs. They established the first large neighborhoods west of downtown – Piggsville, Merrill Park, and Concordia. Most workers walked to work carrying lunch pails and were known as the “bucket brigade.” The neighborhood southwest of the Valley, Silver City, owes its name to the employees of the Valley's Milwaukee Road Shops. The Shops paid its workers in silver dollars, and on pay day there would be a flurry of silver dollars changing hands in all the saloons along National Avenue.

Then - the bridge that carried workers from Silver City to work in the Milwaukee Road Shops

Now - Valley Passage Bridge, one of the three bridges to Three Bridges Park

By the 1960s, the Menomonee Valley was a cultural divide of black and white communities, often known as “Milwaukee’s Mason Dixon line.” In 1967, Father James Groppi, a Catholic priest, led the first of the open housing marches across the Valley’s 16th Street Viaduct in protest of racial discrimination and housing segregation. The Milwaukee Common Council passed an open housing ordinance in 1968. In 1988, the 16th Street Viaduct was officially renamed the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge.

Degradation in the Valley

By the mid- to late-1900s, as shipping transitioned from rail to truck, jobs moved, and manufacturing practices changed, the Valley was left a blighted area with abandoned, contaminated land and vacant industrial buildings. Bridges into the Valley were demolished as businesses left and the Valley was isolated from the surrounding city, a place to pass over, but not a place to go. The neighborhoods adjacent to the Valley most strongly felt the impacts of degradation in the Valley; residents suffered from limited access to jobs and recreation opportunities, high levels of asthma and obesity, and poor air quality.

Vacant buildings at the former Milwaukee Road Shops site, directly east of where American Family Field is located today

Redevelopment Efforts

In 1990, more than 150 years after they were forcibly removed from their homeland, the Potawatomi people regained seven acres of land in Milwaukee’s Menomonee River Valley. At that time, the site was literally a dump. The tribe went to work to remove the vehicles and clean up the land. They opened Potawatomi Bingo a year later. Since then they have been instrumental in the Valley’s redevelopment through advocacy, planning, investments in their property, and financial support for district-wide redevelopment, while also becoming Wisconsin’s most visited destination. Learn more about Potawatomi Hotel & Casino’s history.

“Every tribe, every person, and individual has a history and ours for the last 150 years has been a very long, hard, and depressing history…so it’s very gratifying for us to come back to our homelands to reestablish ourselves.”

In 1998, the City of Milwaukee, the Menomonee Valley Business Association and the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District prepared a land use plan for the Menomonee River Valley, a road map for its redevelopment. At the time, the State of Wisconsin was laying the groundwork for the Hank Aaron State Trail. As a result of these planning efforts, Menomonee Valley Partners was formed as a nonprofit organization, a public-private partnership to facilitate business, neighborhood, and public partners in efforts to revitalize the Valley.

Since 1999, more than 70 companies have moved to or expanded in the Valley, 5,400 jobs have been created, 45 acres of native plants, seven miles of trails, and a nationally recognized shared stormwater system have been established. In addition, 10 million people visit the Valley each year. Hundreds of individuals and organizations have donated their time and talent by serving on boards, committees, and working teams, while thousands of individuals have volunteered at Valley events.

Today, the Valley is a national model of economic and environmental sustainability. Recognized by the Sierra Club as "One of the 10 Best Developments in the Nation," the Menomonee River Valley continues to receive local and national recognition.

Aerial of the Valley from American Family Field looking east toward Lake Michigan

The 6th Street Viaduct was deconstructed and replaced with the 6th Street bridges in 2002, providing the first opportunity for most to actually enter the Menomonee Valley. Read more here. (Photo: David LaHaye)

The Valley's Future

Over 18 months, Menomonee Valley Partners and the City of Milwaukee held public meetings and met with hundreds of stakeholders to envision what the Menomonee River Valley will become in the next 20 years. The City of Milwaukee Common Council approved the Valley 2.0 Plan in June 2015. Partners are working toward this vision now.

In Studies & Reports, you’ll find a list of studies on the Valley’s revitalization dating back to 1998.